In my previous post, I touched on model explainability. One approach for feature attribution is called SHAP, SHapley Additive exPlanations. In this post I will cover my first experiment with SHAP, building on one of my previous notebooks. My GitHub repo containing all of my Jupyter notebooks can be found here: GitHub – wcaubrey/learning-naive-bayes.

What is SHAP

SHAP (SHapley Additive Explanations) is a powerful technique for interpreting machine learning models by assigning each feature a contribution value toward a specific prediction. It’s grounded in Shapley values from cooperative game theory, which ensures that the explanations are fair, consistent, and additive.

What SHAP Does

- It calculates how much each feature “adds” or “subtracts” from the model’s baseline prediction.

- It works both locally (for individual predictions) and globally (across the dataset).

- It produces visualizations like force plots, summary plots, and dependence plots.

What SHAP Is Good For

- Trust-building: Stakeholders can see why a model made a decision.

- Debugging: Helps identify spurious correlations or data leakage.

- Fairness auditing: Reveals if certain features disproportionately affect predictions for specific groups.

- Feature attribution: Quantifies the impact of each input on the output.

Ideal Use Cases

- Tree-based models (e.g., XGBoost, LightGBM, Random Forest)

- High-stakes domains like healthcare, education, finance, and policy

- Any scenario where transparency and accountability are critical

My notebook changes

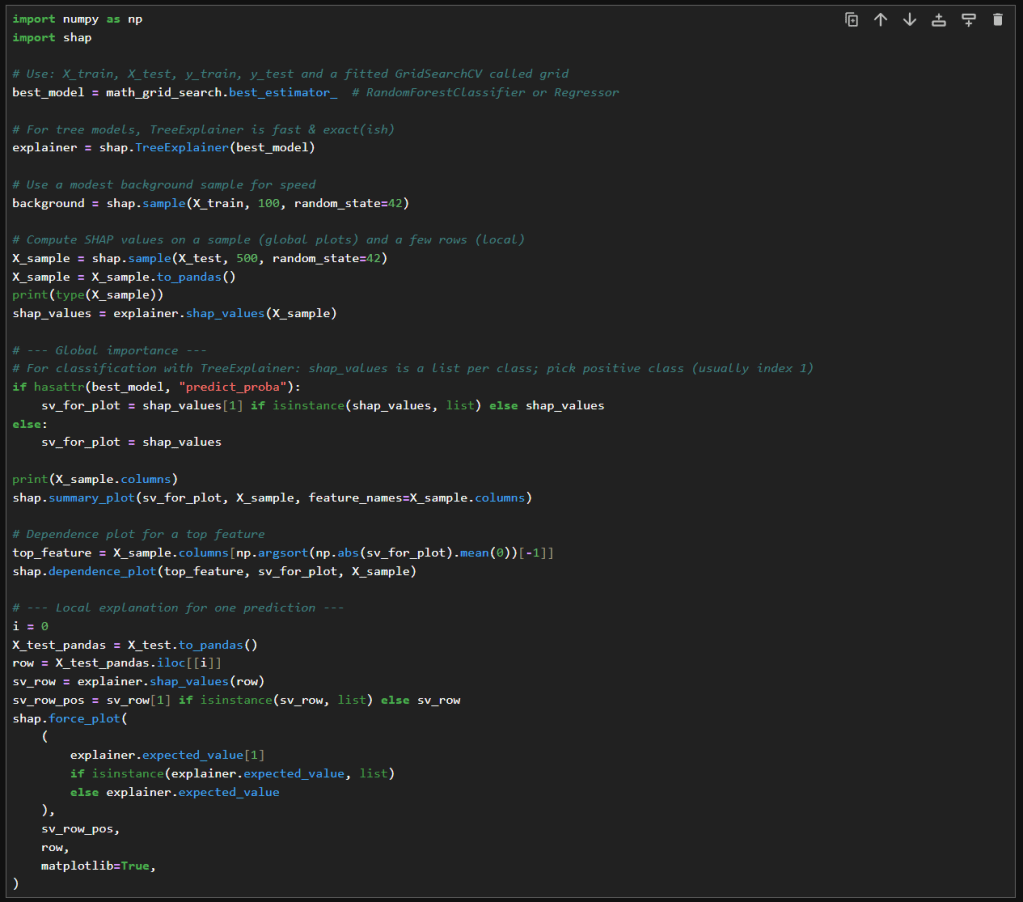

In this new cell, I use the results of the previous grid search to create a SHAP TreeExplainer from the shap package. With that I create three different types of plots: a summary beeswarn, dependence and force plot.

SHAP Visualizations

Interpreting the summary beeswarm plot

The x-axis shows the SHAP values. Positive values push the prediction higher, towards the positive class or higher score. Negative values push the prediction lower.

The y-axis shows the features, ranked by overall importance. The most important features are at the top. The spread of SHAP values shows how much influence that feature can have. The wider the spread of dots along the x-axis, the more variability that feature contributes to predictions. Narrow spreads mean the feature has a consistent, smaller effect.

Each dot represents a single observation for the feature. The color of the dots shows the feature value. Red for high values and blue for low.

If high feature values (red dots) cluster on the right (positive SHAP values), then higher values of that feature increase the prediction. If high values cluster on the left, then higher values decrease the prediction. Blue dots (low feature values) show the opposite effect.

Overlapping colors can suggest interactions. For example, if both high and low values of a feature appear on both sides, the feature’s effect may depend on other variables.

Interpreting the force plot

The base value is the average model prediction if no features were considered. It’s like the starting point. It is the neutral prediction before considering any features.

Arrows or bars are the force each feature contributes positively or negatively to the prediction. Each feature either increases or decreases the prediction. The size of the arrow/bar shows the magnitude of its effect.

- Red (or rightward forces): Push the prediction higher.

- Blue (or leftward forces): Push the prediction lower.

The final prediction is the sum of the baseline plus all feature contributions. The endpoint shows the model’s actual output for that instance

– William