In this blog post, I’m building on my previous work with the Student Alcohol Consumption dataset on Kaggle. My latest experiments can be found in the updated Jupyter notebook. In this updated analysis, I explored several new approaches—including using linear regression, stacking models, applying feature transformations, and leveraging visualization—to compare model performances in both prediction and classification scenarios.

Recap: From the Previous Notebook

Before diving into the latest experiments, here’s a quick overview of what I did earlier:

- I explored using various machine learning algorithms on the student alcohol dataset.

- I identified promising model combinations and created baseline plots to display their performance.

- My earlier analysis provided a solid framework for experimentation with stacking and feature transformation techniques.

This post builds directly on that foundation.

Experiment 1: Using Linear Regression

Motivation:

I decided to try a linear regression model because it excels at predicting continuous numerical values—like house prices or temperature. In this case, I was curious to see how well it could predict student grades or scaled measures of drinking behavior.

What I Did:

- I trained a linear regression model on the dataset.

- I applied a StandardScaler to ensure that numeric features were well-scaled.

- The predictions were then evaluated by comparing them visually (using plots) and numerically to other approaches.

Observation:

Interestingly, the LinearRegression model, when calibrated with the StandardScaler, yielded better results than using Gaussian Naive Bayes (GNB) alone. A plot of the predictions against actual values made it very clear that the linear model provided smoother and more reliable estimates.

Experiment 2: Stacking Gaussian Naive Bayes with Linear Regression

Motivation:

I wanted to experiment with stacking models that are generally not used together. Despite the literature primarily avoiding a combination of Gaussian Naive Bayes with linear regression, I was intrigued by the possibility of capturing complementary characteristics of both:

- GNB brings in a generative, probabilistic perspective.

- Linear Regression excels in continuous predictions.

What I Did:

- I built a stacking framework where the base learners were GNB and linear regression.

- Each base model generated predictions, which were then used as input (meta-features) for a final meta-model.

- The goal was to see if combining these perspectives could offer better performance than using either model alone.

Observation:

Stacking GNB with linear regression did not appear to improve results over using GNB alone. The combined predictions did not outperform linear regression’s stand-alone performance, suggesting that in this dataset the hybrid approach might have introduced noise rather than constructive diversity in the predictions.

Experiment 3: Stacking Gaussian Naive Bayes with Logistic Regression

Motivation:

While exploring stacking architectures, I found that combining GNB with logistic regression is more common in the literature. Since logistic regression naturally outputs calibrated probabilities and aligns well with classification tasks, I hoped that:

- The generative properties of GNB would complement the discriminative features of logistic regression.

- The meta-model might better capture the trade-offs between these approaches.

What I Did:

- I constructed a stacking model where the two base learners were GNB and logistic regression.

- Their prediction probabilities were aggregated to serve as inputs to the meta-learner.

- The evaluation was then carried out using test scenarios similar to those in my previous notebook.

Observation:

Even though the concept seemed promising, stacking GNB with logistic regression did not lead to superior results. The final performance of the stack was not significantly better than what I’d seen with GNB alone. In some cases, the combined output underperformed compared to linear regression alone.

Experiment 4: Adding a QuantileTransformer

Motivation:

A QuantileTransformer remaps features to follow a uniform or a normal distribution, which can be particularly useful when dealing with skewed data or outliers. I introduced it into the stacking pipeline because:

- It might help models like GNB and logistic regression (which assume normality) to produce better-calibrated probability outputs.

- It provides a consistent, normalized feature space that might enhance the meta-model’s performance.

What I Did:

- I added the QuantileTransformer as a preprocessing step immediately after splitting the data.

- The transformed features were used to train both the base models and the meta-learner in the stacking framework.

Observation:

Surprisingly, the introduction of the QuantileTransformer did not result in a noticeable improvement over the GNB results without the transformer. It appears that, at least under my current experimental settings, the transformed features did not bring out the expected benefits.

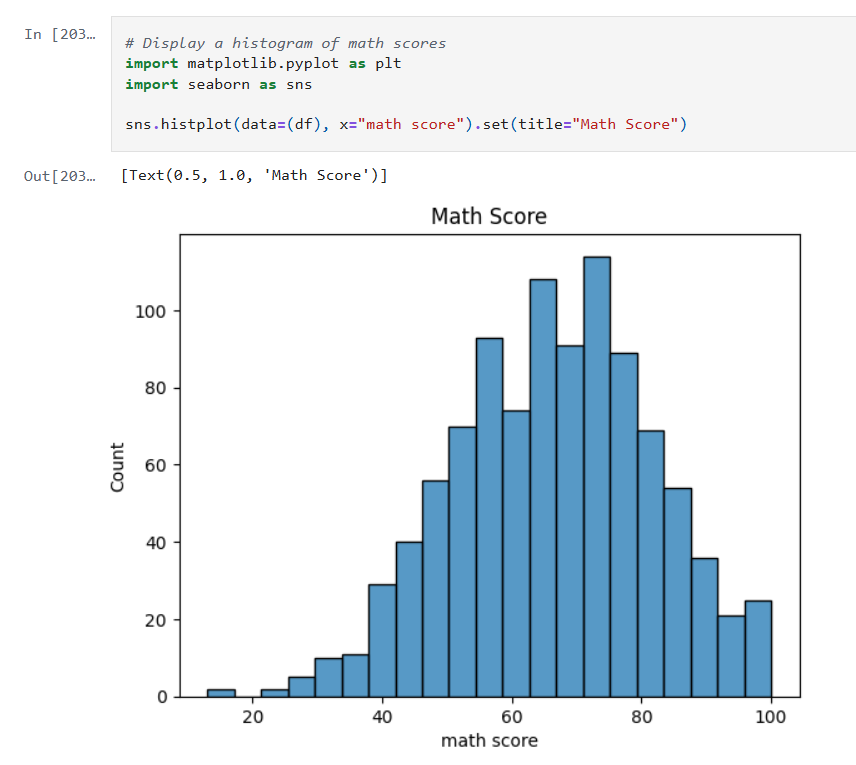

Experiment 5: Visualizing Model Results with Matplotlib

Motivation:

Visual analysis can often reveal trends and biases that plain numerical summaries might miss. Inspired by examples on Kaggle, I decided to incorporate plots to:

- Visually compare the performance of different model combinations.

- Diagnose potential issues such as overfitting or miscalibration.

- Gain a clearer picture of model behavior across various scenarios.

What I Did:

- I used Matplotlib to plot prediction distributions and error metrics.

- I generated side-by-side plots comparing the predictions from linear regression, the stacking models, and GNB alone.

Observation:

The plots proved invaluable. For instance, a comparison plot clearly highlighted that linear regression with StandardScaler outperformed the other approaches. Visualization not only helped in understanding the behavior of each model but also served as an effective communication tool for sharing results.

Experiment 6: Revisiting Previous Scenarios with the Stacked Model

Motivation:

To close the loop, I updated my previous analysis function to use the stacking model that combined GNB and logistic regression. I reran several test scenarios and generated plots to directly compare these outcomes with earlier results.

What I Did:

- I modified the function that earlier produced performance plots.

- I then executed those scenarios with the new stacked approach and documented the differences.

Observation:

The resulting plots confirmed that—even after tuning—the stacked model variations (both with linear regression and logistic regression) did not surpass the performance of linear regression alone. While some combinations were competitive, none managed to outshine the best linear regression result that I had seen earlier.

Final Thoughts and Conclusions

This journey into stacking models, applying feature transformations, and visualizing the outcomes has been both enlightening and humbling. Here are my key takeaways:

- LinearRegression Wins (for Now): The linear regression model, especially when combined with a StandardScalar, yielded better results compared to using GNB or any of the stacked variants.

- Stacking Challenges:

- GNB with Linear Regression: The combination did not improve performance over GNB alone.

- Stacking GNB with Logistic Regression: Although more common in literature, this approach did not lead to a significant boost in performance in my first attempt.

- QuantileTransformer’s Role: Despite its promise, the QuantileTransformer did not produce the anticipated improvements. Its impact may be more nuanced or require further tuning.

- Visualizations Are Game Changers: Adding plots was immensely helpful to better understand model behavior, compare the effectiveness of different approaches, and provide clear evidence of performance disparities.

- Future Directions: It’s clear that further experimentation is necessary. I plan to explore finer adjustments and perhaps more sophisticated stacking strategies to see if I can bridge the gap between these models.

In conclusion, while I was hoping that combining GNB with logistic regression would yield better results, my journey shows that sometimes the simplest approach—in this case, linear regression with proper data scaling—can outperform more complex ensemble methods. I look forward to further refinements and welcome any ideas or insights from the community on additional experiments I could try.

I hope you found this rundown as insightful as I did during the experimentation phase. What do you think—could there be yet another layer of transformation or model combination that might tip the scales? Feel free to share your thoughts, and happy modeling!

– William