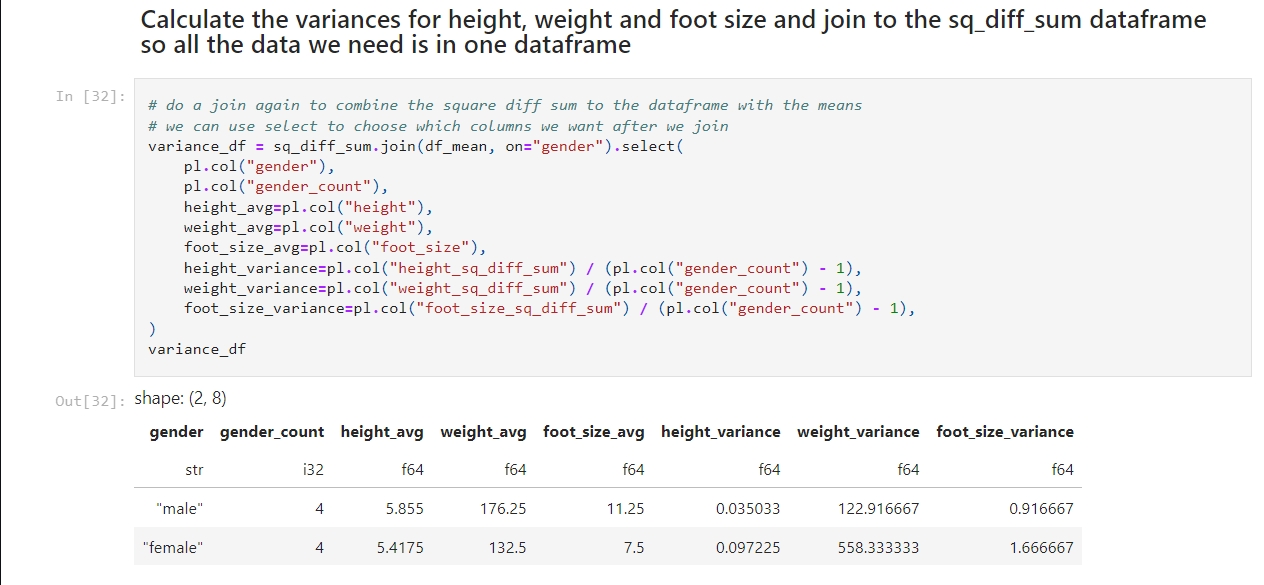

In today’s post, I use scikit-learn with the same sample dataset I used in the previous post. I need to use the LabelEncoder to encode the strings as numeric values and then the GaussianNB to train and testing a Gaussian Naive Bayes classifier model and to predict the class of an example record. While many tutorials use pandas, I use Polars for fast data manipulation alongside scikit-learn for model development.

Understanding Our Data and Tools

Remember that the dataset includes ‘features’ for height, weight, foot size. It also has a categorical field for gender. Because classifiers like Gaussian Naive Bayes require numeric inputs, I need to transform the string gender values into a numeric format.

In my new Jupyter notebook I use two libraries:

Scikit-Learn for its machine learning utilities. Specifically, LabelEncoder for encoding and GaussianNB for classification.

Polars for fast, efficient DataFrame manipulations.

Step 1: Encoding Categorical Variables

The first step is to convert our categorical column (gender) to a numeric format using scikit-learn’s LabelEncoder. This conversion is vital because machine learning models generally can’t work directly with string labels.

Below is the code from our first notebook cell:

In that cell:

- I instantiate a

LabelEncoderobject. - For every feature in

columns_to_encode(in this case, just"gender"), I create a new Polars Series with the suffix"_num", containing the encoded numeric values. - Finally, I add these series as new columns to our original DataFrame.

This ensures that our categorical data is transformed into a machine-friendly format, an also preserves the human-readable string values for future reference.

Step 2: Mapping Encoded Values to Original Labels

Once we’ve encoded the data, it’s important to retain the mapping between the original string values and their corresponding numeric codes. This mapping is particularly useful when you want to interpret or display the model’s predictions.

The following code block demonstrates how to generate and view this mapping:

In that cell:

- I save the original

"gender"column and its encoded counterpart"gender_num". - By grouping on

"gender"and aggregating with the first encountered numeric value, I create a mapping from string labels to numerical codes.

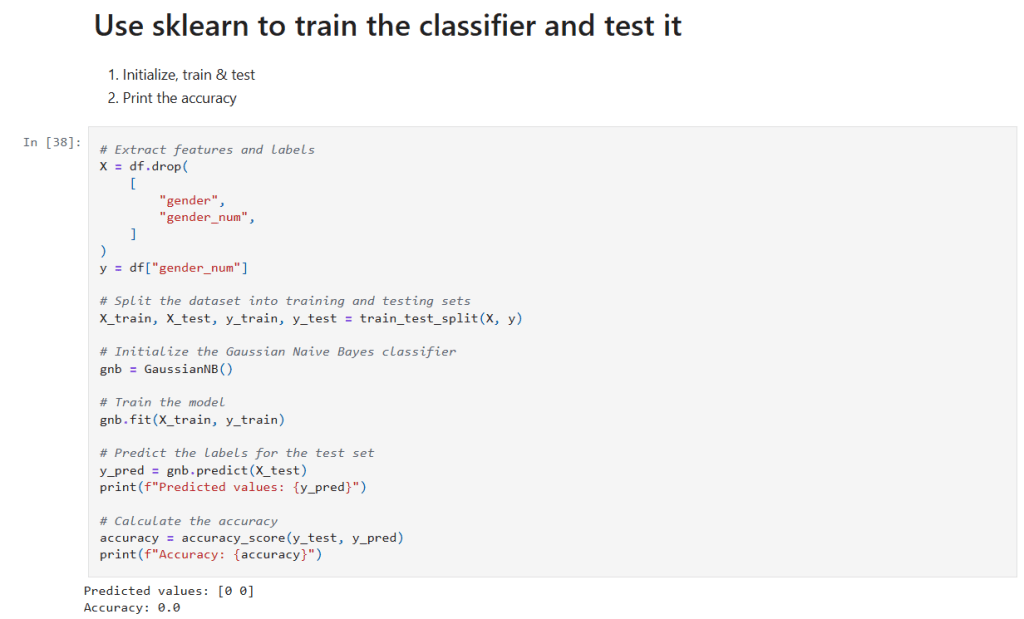

Step 3: Training and Testing the Gaussian Naive Bayes Classifier

Now it’s time to build, train, and evaluate our model. I separate the features and target, split the data, and then initialize the classifier.

In that cell:

- Get the data to use in training: I drop the raw

"gender"and its encoded version from the Dataframe (X) and save the encoded classification in (y). - Data Splitting:

train_test_splitis used to randomly partition the data into training and testing sets. - Model Training: A

GaussianNBclassifier is instantiated and trained on the training data using thefit()method. - Prediction and Evaluation: The model’s predictions on the test set (

y_pred) are generated and compared against the true labels usingaccuracy_score. This gives us a quantitative measure of the model’s performance.

Step 4: Classifying a New Record

Now I can test it on the sample observation. Consider the following code snippet:

In that cell:

- Create Example Data: I define a new sample record (with features like height, weight, and foot size) and create a Polars DataFrame to hold this record.

- Prediction: The classifier is then used to predict the gender (encoded as a number) for this new record.

- Decoding: Use the

gender_mappingto display the human-readable gender label corresponding to the model’s prediction.

Final Thoughts and Next Steps

This step-by-step notebook shows how to preprocess data, map categorical values, train a Gaussian Naive Bayes classifier, and test new data with the combination of Polars and scikit-learn.

The new Jupyter notebook can be found here in my GitHub. If you follow the instructions in my previous post you can run this notebook for yourself.

– William